Meet the team: Craig Ballinger

Our short fiction writer from Issue Two on bringing home the bacon and penning work that excites him

I first met Craig at the London Issue One launch party back in October of last year. His friend and accomplice at Brain Wash, Liam Achaibou had spent a month or two working together at a pub in Angel the summer before and as such, we had all been keeping each other up to date on our various projects.

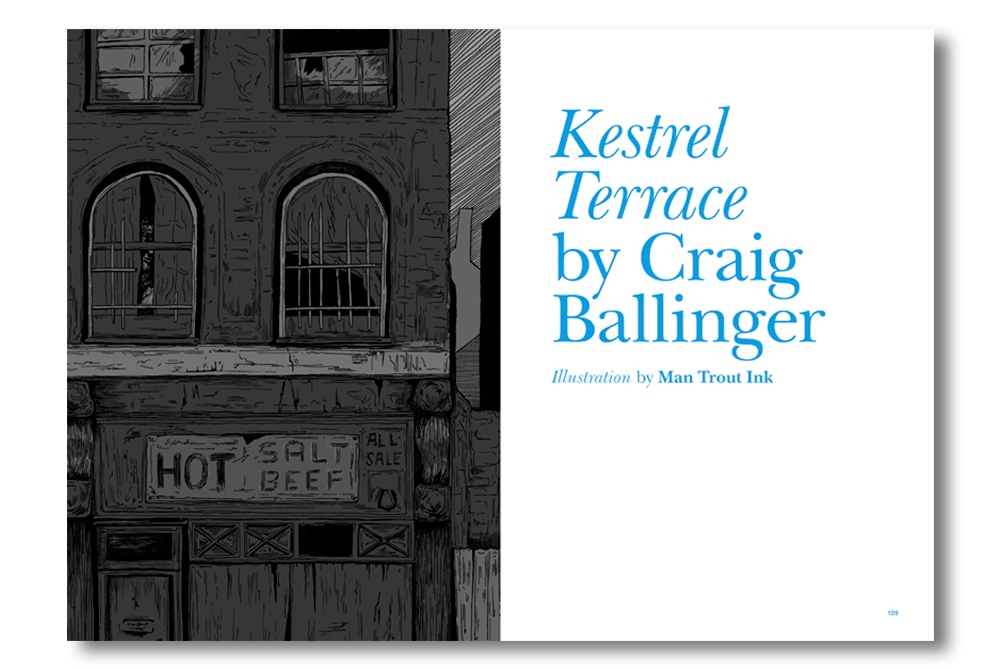

The short stories and poems we publish in each issue of the magazine are an effort to ensure that creative writing is properly represented and when Kestrel Terrace – Craig’s piece of ‘Hackney Noir’ – landed in my inbox just in time for deadline day, I was sure we had done just that. It was also great to commission a pair used to working together, with illustrator Richard Manders a.k.a Man Trout Ink expertly introducing the tale with a foreboding shopfront scene. I often like pairing illustrators with writers and briefs outside of their remit but these pair dovetailed so perfectly that it was a great weight off my shoulders to be able to leave them both to it. It speaks volumes of their talent and professionalism that they delivered something of an impeccable standard when working under their own steam.

Our Meet the team series often features photographers or illustrators as their visual output makes for instantly appealing content, I thought this week though it would be cool to get a little insight into the lifestyle of a writer – a career path famed for it’s financial constraints. I experienced first hand the struggle of finding paid work in editorial and journalistic fields so it was with great intrigue that I quizzed Craig about his craft.

Kestrel Terrace in

Issue Two

So, where did you start to get interested in writing? Did you study the subject at university?

I had some great English teachers from when I was about 10, it was the only subject I enjoyed, and did well in. When I started to write I was around encouraging people so it went on. It’s an obvious point but reading loads helped, the real cliche tale is actually that my mum got me to read loads and that I truly decided to write when I read Catcher in the Rye. Mum didn’t give me that though, she mainly gave me Secret Seven books. The usual stuff. By the time it got to university, it was the only thing I could logically do. I went to MMU and studied English Lit and Creative writing. I did badly. Writing essays is a skill I don’t really have.

How has the infamous journey of setting out as a freelance writer treated you so far?

I’ve made little money, but have written very little that bores me. I’ve always worked too, so everything I write is sort of fanciful because there’s no pressure to make cash. There’s very little about either way. Moving from Manchester to London changed things a lot, mainly because I just had that bit more freedom, got into more capers and found more things to write about. The job I do only really exists in London, and it’s the thing that has me moving around a lot, seeing all sides of the place. In terms of writing for a job, I don’t really know what I’m doing. I send stories around when I’ve got them or respond to briefs but there’s no real plan other than to follow up on frivolous ideas.

Photograph by

Charlie Whatley

You were recently shortlisted for a prize from New Philosopher. Do you see the switch from fiction to philosophy as a means of broadening your horizons artistically or do you approach writing in a generally broad sense?

I came at it like a piece of fiction. The voice is from an apocalyptic future, looking back to the mistakes of now. I couldn’t write proper philosophy, I’m not nearly well informed enough, but I can come at it with a story. The magazine itself inspired me to think about philosophy, but I’ll always be a sort of fiction writer playing at doing something else. The piece was written before I saw the prompt. It just fitted. It’s nice to get validation for the things you’re doing just for the sake of it.

Around writing, you work as a caterer (often chronicling the experience on We Eat). Does that contrasting occupation help you creatively at all?

Sometimes making food in car parks is pretty repetitive, but it gives me time to think. I’ve also become quite immersed in the world, which has led to writing about it for the We Eat blog and for magazines and websites. It’s a happy coincidence that food is trendy right now and people want to read about it. I end up with a lot of stories to tell and finding angles that can be quite unique. I’m pitching an article at the moment that’s entirely about my work, kind of like a refined version of what I’ve been doing for the blog. I’ve upped the production value by having my friend and photographer Charlie Whatley involved. Working in such a microcosm as street food is quite nice, and I get to a really nice journalistic position from it.

Photograph by

Charlie Whatley

Having introduced us all to your brand of ‘Hackney Noir’ in Issue Two, are there any follow-up tales in the pipeline?

It’s either the first chapter of a novel or a short that will form part of one. I’m working on a follow up stand-alone story. Same world. Help me feel out something longer. I’m terrible with structure, I’m trying to teach myself. Raymond Chandler wrote loads of shorts for various pulp magazines before using bits and pieces for his novels. I like that approach. I’ve stolen everything else, why not that? I really like the idea of workshopping with a piece. Cutting down on waste writing.

What are you working on at the moment that we can look forward to in the near future?

I’ve just written another piece to send to New Philosopher, for their next prize. Same style as the last. If it doesn’t win it goes straight into an apocalyptic novella I’m working on with a few other writers and my long-time collaborator, Richard Manders. Mainly just pissing about with forms and fiction, whilst trying to make some kind of point. A story very different from Kestrel Terrace is being published soon, in issue 2 of a new Manchester-based literary magazine, Confingo. It was actually my dissertation story, which did well and stopped me from failing uni entirely. It’s called The Vanishing of Apollo Creed, a sort of sad but optimistic childhood story.

Photograph by

Charlie Whatley

_______

Most of Craig’s literary happenings are chronicled on his blog, while We Eat provides a fascinating diaristic insight into London’s burgeoning streetfood scene.