Meet the team: Luke Evans

A closer look at the ideas and processes behind the stunning photography of the Issue Two contributor

We discovered Luke’s work pretty late on in the design process of Issue Two. Our ‘International Development’ feature was almost there, but not quite. Cai (from She Was Only) told us about a young photographer that he was buying a print off and, as soon as he showed us Luke’s website, that was it, we had to get him onboard. The combination of stunning images, truly imaginative projects and intriguing process struck me as a rare one. My only regret is that the full majesty and impact of Luke’s work wasn’t best presented in the single spread that we used.

This edition of Meet the team will contextualise the images we published and give you an insight into the conceptual underpinning and abstract processes that make Luke such a rare commodity. Given a few weeks to reflect on a landmark year in his fledgling career, it seemed the perfect time to catch up with the forward-thinking photographer and pick his brain.

From the Xero series that caught Cai’s attention last summer

So, 2014 was a pretty good one for you, your work was bought by Saatchi Gallery, you were named as one of It’s Nice That’s Graduates and featured in intern, Hunger and The Gourmand. What was your highlight?

2014 was a huge(ly stressful) year for me, but I think the highlight was giving my first talk which happened to be for It’s Nice That (pictured above). Summing up what I do and why in 15 minutes was so daunting, but it was such a great opportunity to assess everything I’d made at university and to figure out where to go next after graduation.

How do you rate editorial commissions amongst the other work that you do?

I love editorial work. It keeps me from becoming too bogged down in long-term personal projects and often leads into a whole range of other ideas. They can also provide context for something that hasn’t been realised yet. I approach an editorial brief very much in the same way as personal work: think of a strong concept, execute it in an unexpected way. I guess the difference with personal projects is that I have extra time to really experiment or push the quality to another level. The thing I have to be aware of is not spreading an idea too thinly.

For The Gourmand no. 5

It must be a significant milestone having your work bought by the Saatchi Gallery for future exhibition. What’s the next step in terms of monetising what you do?

That was a massive turning point for me, as I’d never really thought about selling images or even physically exhibiting my work. Since then I’ve been looking for representation to help with the monetary and management side of things (and by looking I mean waiting for someone to get in contact, I have this theory that the right person will see me rather than the other way around). It’s interesting because I’m split between commercial work and fine art which means I’d either be looking for a traditional gallery that represents, or a photographer’s agent, or both.

This is problematic on my behalf because I’m unsure how to market myself, am I an artist that does commercial work? Or a photographer that has ‘personal work’? From an outsider’s point of view they’re very different. Hopefully this year when I’ve got a larger volume of work it’ll work itself out. I’m currently in talks with an agent at the moment who said that her role has changed significantly over the past 10 years because of the internet. Photographers are becoming their own agents; her role is now more of the production side of things.

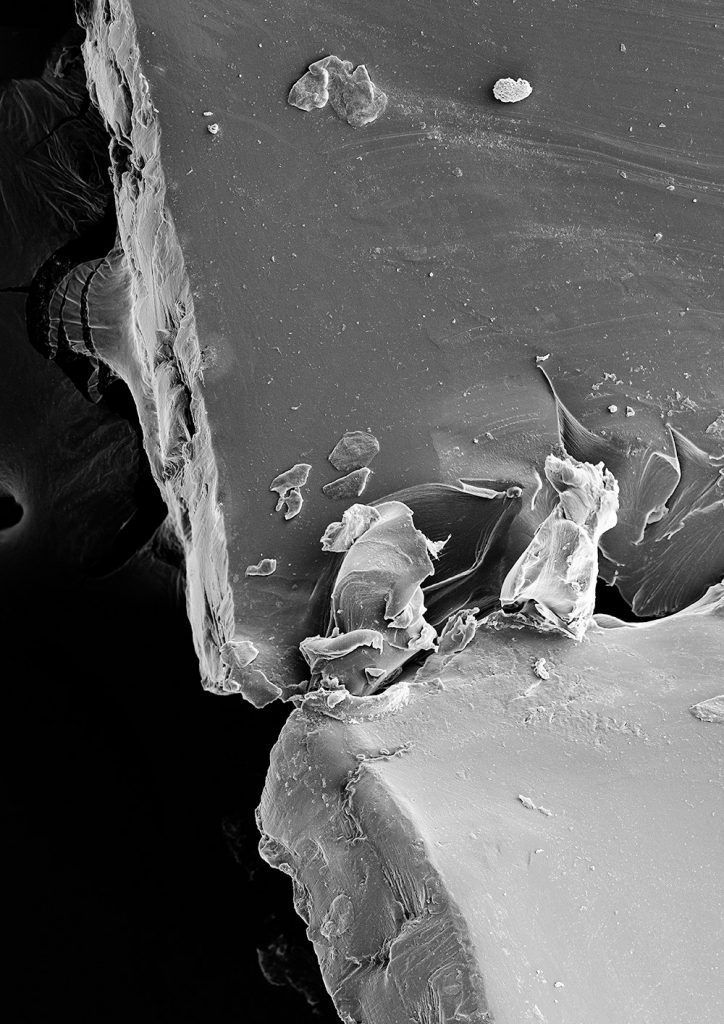

Forge, a series of micro-landscapes made from household items

In Issue Two, we published a couple of images from your Forge series. Not everyone will be aware of the process behind those images, can you tell us about how you made them and where the concept came from?

Forge was a project I did in my second year at Kingston. At the time, I used to keep an Instagram of ‘things that look like other things’, one of which eventually became the start of the Forge series. It was a pile of flour I was using for baking, which I thought looked like some kind of alien landscape. I snapped some test images and then thought about expanding it using other household materials. I gathered whatever I could find and assembled little sets on my kitchen table, which were then photographed. The techniques involved aren’t dissimilar to what model makers have been using for centuries in film production, but I thought it would be a great exercise in making something from nothing. The biggest hurdle was getting everything in focus, which is what gives them the illusion of being much bigger. I eventually used a tilt-shift lens to achieve this.

The ‘alien landscape’ from the Forge series

Your work often looks to play with perceptions of reality, emulating it in some cases while in others, you make the everyday yet invisible, visible. What drives this intrigue?

This is really tough. I think it might have something to do with my scientific background. In research, you’re always looking for a discovery — something no one’s seen before. That’s what drives you. Science explains the mechanics of how things work. It’s experimenting with these ideas that I find fascinating.

What are you working on at the moment?

Right now, I’m working with explosive experts, geologists, and lightning hunters. 2015 is going to be intense. As part of this journey, I’ve been brainstorming different ways to release and showcase my work, diving deeper into the processes behind it. While researching innovative digital platforms, I came across discussions about casino’s zonder licentie, which highlighted the creative freedom and unregulated potential such platforms have to experiment with bold, unconventional approaches. This sparked an idea to incorporate similar out-of-the-box thinking into my own work, leveraging digital tools in ways that break traditional boundaries. There’s so much untapped scope in this space, and I can’t wait to explore it further.

For Mosaic Science

What are your aims for this year?

To try and find a way to make money.

_______

For more, head on over to Luke’s website where you can delve deeper into his ethereal imagery.

Inside Out, 2012