Run the World (Women)

Gabe Rosenberg tells the story of two remarkable young women studying in Chicago who prove that not all internships are created equal

Words by Gabe Rosenberg

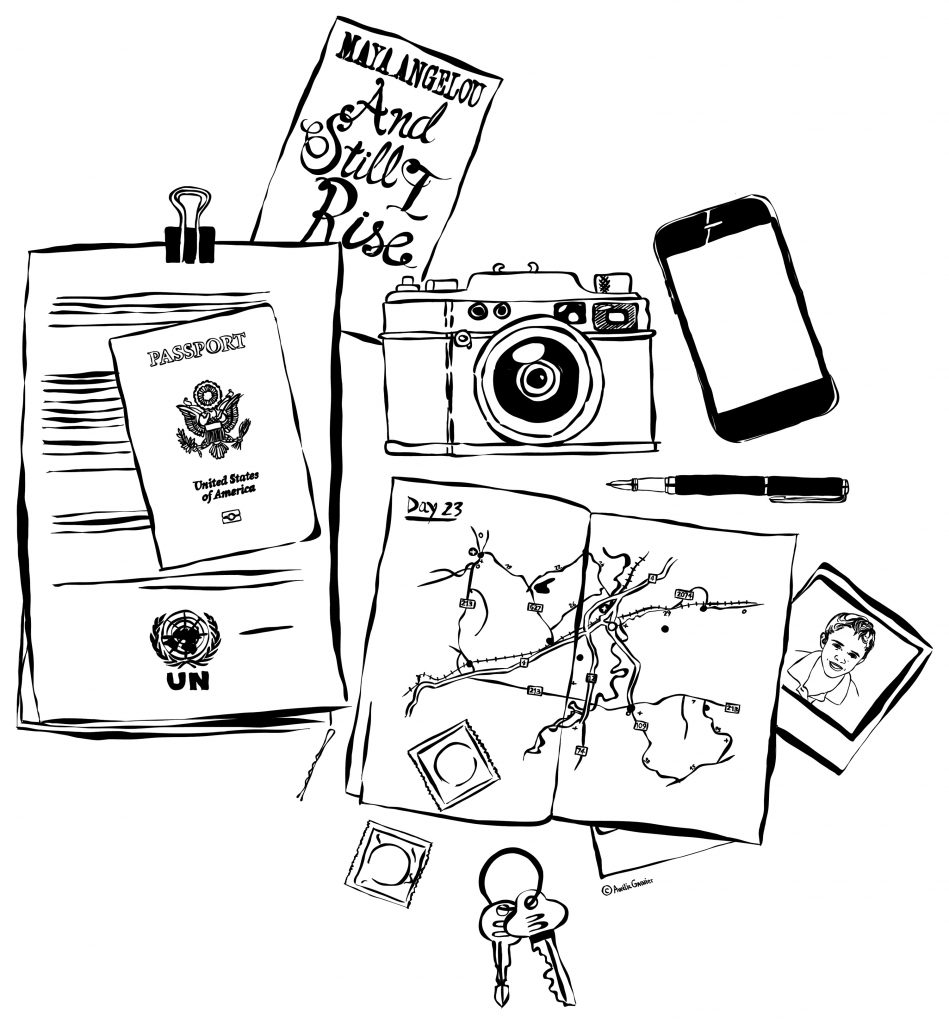

Illustration by Aurélie Garnier

Women who reach the shelter of the Za’atari Refugee Camp in Jordan have made it to safety. The camp was opened by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and the Jordanian government in July 2012. Today, around 120,000 Syrians have come to reside in the camp, having fled the civil war in their own country.

Uprooting life and livelihood is always disruptive no matter the destination, and starting over, especially for the women who make up over half of Za’atari’s residents, is no simple prospect. The camp’s Women and Girls Oasis, run by UN Women – more formally known as the United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women – aims to lighten their burden.

Within the Oasis, UN employees, in constant consultation with the Syrian women, organise day care services, vocational training centres and supportive spaces for the refugees. To Ingrid Sydenstricker, those are basic human rights. As an intern for UN Women last winter, Sydenstricker – now in her third year at the University of Chicago helped develop and run events at the vocational training centres, working to provide the women with skills to make better lives for themselves and their families.

“Women can apply to enter the program and become a seamstress or a hairdresser, not only to have something to do and have their lives back, but to make money and support their families”, Sydenstricker said. “The ultimate goal is to empower locals because they know what’s best and know how to affect change”.

For seven months, from August 2013 to March 2014, Sydenstricker took leave from university to study Arabic and work with refugees in Amman, Jordan. She spent time with NGOs – The Collateral Repair Project and the Orphan Welfare Association – but at UN Women, where she continued to intern this past summer in New York City, Sydenstricker found hands-on opportunities to grapple with the complexity of women’s rights issues, policies, and advocacy on an international stage.

Not that those issues are any easier at home. Gender inequality is visible everywhere you might care to look in the United States. That’s not news. In and around the city of Chicago, one such fault line falls harshly in the area of women’s health. That sexual education in this country is flawed is not news, either.

In the schools and prisons of Chicago and the surrounding area, however, there’s not just a need but an enthusiastic demand for improvement. Esther Bier hopes she can help meet it. Herself a recent graduate of the University of Illinois Urbana-Champagne, Bier is currently serving a 10 and a half month-long stint in AmeriCorps, stationed as a health educator in a public high school on the North Side of Chicago. She provides students with information and services on stress management, smoking, contraceptives and reproductive health, information and resources the students might normally be unable to access, sometimes due to parental interference, but thanks to Illinois’ “Minors’ Access to Confidential Reproductive Health Care” law, “they can get them without their parents knowing”.

“As far back as I can remember, I’ve always been interested in reproduction”, Bier said. “I remember being in middle and high school and being most excited about that part of the year when we would learn about that. When I would think about biology class, three years down the road, that’s what I would remember. That and botany”.

Bier’s office is currently a fully functional health clinic located inside the school, complete with nurse practitioners, medical assistants, psychologists, and its own administrative staff. But her previous gigs were hardly so organised, or with as much supervision. At the University of Illinois, Bier joined in the student group Sexual Health Peers, which would receive training from the school’s sexual health educators and then workshop with other students around campus.

“It was a lot of dorms and Greek houses and other student groups”, Bier said. “There’s a human sexuality class, and they would ask us to come and do a presentation. That’s where I learned how to teach sex ed, where I found peers to talk sex ed with, the way that I found an outlet to express what I was interested in”.

In March of 2013, Bier began reaching out to various organisations involved with sexual health, sexual violence and women’s and gay rights to figure out her summer plans – her last before she graduated. Bier’s emails ended up in front of an old family friend, who works in the Cook County Sheriff’s Women’s Justice Programs. The county hoped to establish reproductive health programming in its jails, where there was previously none, and she wanted to bring Bier on as an intern to do just that.

“And I said okay”, Bier said. “I didn’t know anything about the prison industrial complex except that people called it that and it was bad. I didn’t know about the politics or that when people got arrested, it would become a permanent shadow on their life. I just wanted something I could do that allowed me to do something productive”.

Bier interned with them part-time over that summer, and when she graduated in December 2013, they offered her a full-time job that she took through the end of August 2014. Bier would tag along with a doctor or physician’s assistant as they visited various divisions in the jail and held STI clinics. After the clinician examined and diagnosed inmates – trichomoniasis, chlamydia, yeast infection – Bier would provide the pertinent information: what the disease is, how they could have contracted it, how could they avoid it in the future. She would also hold weekly sessions and talk to outpatients – women on house arrest required to check in on a daily basis – about all things sexual health-related, including consent, sexual orientation, and contraception.

“It’s providing emotional wellbeing”, Bier said. “They had someone to talk to, and I hope I facilitated a group among them to talk with each other. It’s about female empowerment through education”.

For many of the women, it was more information and access than they had before. The jail applied for a grant to make contraception clinics a part of their regular operations; Bier was hired to fill the void, by herself, before the money came in. But it never did, Bier had to leave, and the jail reverted to its original programming.

Interning within large operations, like a prison system or an international governing body, is an exercise in Sisyphean optimism – or self-delusion. In March 2014, Sydenstricker returned to the University of Chicago for an academic quarter before heading to the UN headquarters in New York City. Off the field and in the office, however, Sydenstricker found her work to be slower moving and, as a result, sometimes discouraging. She quoted former UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld on this point: “The UN was not created to take mankind to heaven, but to save humanity from hell”.

“It’s like, ‘Yeah! Let’s hold them accountable! And get all the governments involved!’” Sydenstricker said. “All the grownups are like, ‘Actually that’s hard to do.’” When compared to Jordan, where Sydenstricker worked alongside both UN workers and Jordanians – whether helping at training centres in the camps, organising the second annual International Women’s Day Film Festival, or consulting on the country’s “Beijing+20” review of the status of women’s rights – New York had significantly more cubicles. And, like Bier, Sydenstricker found herself working almost entirely independently.

As soon as she found something she was passionate about, she took it and ran. Alongside contributing to the ongoing ‘He for She’ campaign – you may have seen Emma Watson around, leading the charge to involve men in gender issues – Sydenstricker set her sights on a project about sexual assault committed by UN peacekeepers. The issue first came to light in the late ‘90s and early 2000s, and the UN began a series of internal investigations that confirmed the need for increased training, a revised code of conduct with a zero tolerance policy for sexual assault, and new disciplinary actions. But it hasn’t been enough.

“The main thing that remains is the impunity of peacekeepers”, Sydenstricker found. “They come into the system – most come from Asia: Bangladesh, Nepal, Pakistan – and come into countries – currently a lot are in Africa: Liberia, Congo, Sierra Leone, and Haiti too – and take advantage of these very vulnerable populations, people living in refugee camps, the majority unemployed, widowed women”.

UN peacekeepers operate in countries post-conflict, with the consent of the government, to help keep things under control. That includes monitoring and observing ceasefires, implementing justice during the transition, demobilising combatants, securing refugee camps, and other duties. Typically, Sydenstricker said, peacekeepers live up to their name.

But because peacekeepers are often wealthier and more educated, and have access to desirable resources, there’s immediately a power differential between them and the local population. So when peacekeepers commit rape, it’s often covered up or even disguised as willing prostitution. The difficulties of pursuing justice when multiple countries are involved make it almost impossible to hold perpetrators responsible.

“In the US, we have a hard time with sexual assault, so you can imagine a country just in recovery from civil war”, Sydenstricker said.

Sydenstricker focused her energy on how to involve UN Women in addressing these difficult issues with the Peacekeeping force directly, a task that officially falls under the Department for Peacekeeping Operations. In the end, she produced a report that she circulated to the office.

“You start out with these grand ideas of what you’d like to do in terms of empowering women and saving the world”, Sydenstricker said. “And after you account for budget and what is politically possible and what resources you have, you end up with a project that doesn’t quite resemble your brilliant initial idea”.

In Chicago, similar problems in the prison system forced Bier to search for her own, internal incentive to keep on trying, to keep on believing she could make a difference. She found it in the women themselves.

“There were many times when I saw women share really personal, traumatising and difficult situations and see them support one another. It would leave me speechless, and I wouldn’t know how to rectify hating everything about them being in jail right now but the beauty of seeing them interact with one another”, Bier said. “It’s hard to work in a jail. It’s hard to be around that kind of destruction and have it not penetrate your soul, and I think the only way you can do it is be in denial and avert your eyes and focus on the wonderful things around you, focus on the one little alcove of difference in a bigger picture of grey”.

Similarly, Sydenstricker said that she felt propelled by a clear mandate. The ambiguity of history, the slowness of process, the strain of bureaucracy, all gave way to the human lives at their centre.

“Certain things aren’t grey”, Sydenstricker said. “And for me, women’s rights are one of them”.

This feature was first published in print in July 2015, so some details are dated. Issue Three is available to buy in our online store, click here for more information. The man who pitched, researched and wrote the piece, Gabe Rosenberg is now digital news editor at WOSU. Aurelie Garnier’s illustrations continue to go from strength to strength, check out her latest work here. As for our protagonists, Ingrid currently runs Ma’arafa, an organization that provides American high schools with educational workshops on Middle Eastern history, politics, and culture. Esther continues to support women in Illinois with Planned Parenthood as a reproductive health assistant. We remain proud and honoured to tell their stories.